Belfast – On Sunday morning, prominent Irish politician Gerry Adams woke alone in a cell in Antrim police station. By the following evening, the Sinn Fein president was stepping onto a podium at an election rally at the Devenish Centre, West Belfast as an 800-strong crowd chanted his name.

Adams, who smiled widely, did not look like a man who had spent four nights in police custody. He told cheering supporters that his arrest in connection with the 1972 killing of West Belfast mother of ten Jean McConville was “a sham”, but that Sinn Fein would not be diverted from “the job of building the peace”.

The Good Friday Agreement, signed in 1998, ended the 30-year “Troubles” that cost over 3,000 lives. Since 2007, Sinn Fein, the political wing of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), has shared power with the Democratic Unionist Party in a devolved parliament in Belfast.

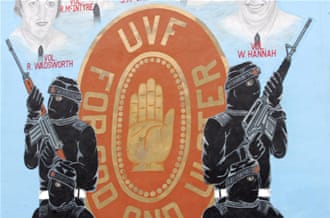

Concerns, however, are being raised about the fragility of the peace in Northern Ireland. The murals and flags that line many streets across this country of just 1.8 million attest to on-going tensions between unionists, who favour a political union between Northern Ireland and the Great Britain, and republicans, who want a united Ireland.

Recent months have been particularly difficult. Attacks by republicans opposed to the peace process have been frequent. Early in the New Year, talks in Belfast brokered by US diplomat Richard Haass to resolve issues of the past, parading, and symbols collapsed without a deal.

In February, the devolved power-sharing government stood on the brink of collapse after the revelation that almost 200 republican paramilitaries wanted for crimes committed during the conflict had mistakenly been issued with letters informing them that they were not being sought by UK authorities.

‘The volcano will erupt’

Just last week, Northern Ireland Secretary of State Theresa Villiers ruled out independent reviews into the killing of eleven civilians by British troops at Ballmurphy in 1971 and a 1978 IRA bombing that left twelve people dead

“The problem now is that events are coming along quicker than [the 1998 peace deal at] Stormont can deal with. In the past there were periods of calmness, now there is no time for recovery,” says Jonny Byrne, a lecturer in criminology at the University of Ulster. “It’s like the early signs of Vesuvius, we know the volcano is going to erupt.”

|

In the past there were periods of calmness, now there is no time for recovery… It’s like the early signs of Vesuvius, we know the volcano is going to erupt. |

International onlookers have wondered aloud whether Northern Ireland might be on the verge of a return to violence. Gary White, a former Police Service of Northern Ireland chief superintendent, says it already has. “Over this last number of years we have had police officers killed, we have had soldiers killed, we have had prison officers killed, we have had many people injured, members of the public, members of the police and other security forces,” White says. “So it is a fact that violence is present in our society.”

An indication of the on-going friction in Northern Ireland came in December 2012. After a vote at Belfast city council to fly the Union flag on designated days rather than all year round, riots broke out in pro-union areas. As streets across the city were blockaded, Belfast effectively came to a standstill.

One of the reasons loyalists, who support the maintenance of the union with Great Britain, are so angry is that they feel they have lost out to republicans in the peace process, says Mark Vinton, a member of the Progressive Unionist Party, which is linked to the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force.

Vinton feels that the peace agreement has allowed republicans to further their political goal of Irish unification. Since 1998, Sinn Fein has become the largest nationalist party in Northern Ireland and is growing in popularity south of the border.

“Sinn Fein and republicanism have used the Agreement as a stepping-stone to further their own aims. So basically anybody that you speak to within a working class Unionist or loyalist community will feel massively let down, that it wasn’t an agreement at all, that there were shafted,” says Vinton.

Paying a peace divident?

Loyalists such as Mark Vinton say their communities have never received the much-vaunted “peace dividend” promised by politicians after the 1998 agreement that ushered in the historic power sharing arrangement between Catholics and Protestants.

“If you come into Belfast city centre you will see [it] flourishing,” he says. “But if you take a 10 minute sidestep to either side of North, South, East, West Belfast, you go into working class areas, you will then see the dividend that was meant to pay off peace-wise, has not paid off in those communities, they still live in mass deprivation.”

Ardoyne, a republican area in North Belfast, regularly ranks as one of the most deprived communities in Northern Ireland. Political tensions here have risen in recent months. Just across the “interface” that separates Catholics from Protestants, a loyalist protest has been ongoing since July, when a parade by the Protestant Orange Order was prevented from passing through a nearby nationalist area.

“Negative elements” are trying to manipulate and exploit tensions over flags and other symbols of identity, says Joe Marlay, a community worker in Ardoyne.

But life has changed for the better since the ceasefires, says Marlay, whose father was shot dead by loyalists. “The life I had sort of growing up, is not the life of my sons and daughters have now in our house. We had bullet-proof [glass] on the doors, and some of the windows, we had security gates on the stairs, we had our own security procedures [for] how we lived…. If we were driven to school in the mornings we had to check under the car for devices.”

Ghosts of the past

Nevertheless, fears are growing that demographic and social changes could put further pressure on the gains of peace. The 2012 census found that, for the first time, Protestants do not constitute a majority in Northern Ireland. Formal education is sorely lacking in working-class Protestant areas, and the local economy is still struggling to recover from the global financial crisis.

|

| Mistrust between unionists and republicans continues despite a peace deal signed in 1998 [EPA] |

Relations between Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party, who share power in the devolved assembly at Stormont, are icy and getting colder with each passing week.

“The principles, the goodwill and ethos of the Good Friday Agreement are gone,” says Dr Jonny Byrne.

The Conservative-led coalition government in London has shown little appetite for involving itself in Northern Irish affairs. Prime Minister David Cameron is from a generation of Tories that have little psychological or emotional attachment to a peace process that was the product of Tony Blair and New Labour.

The failure of the British government – and its Irish counterpart – to engage with the situation in Northern Ireland is creating a power vacuum, says Steven McCaffery, editor of Belfast-based investigative website the Detail.

“The whole premise of the Good Friday agreement was that it was not an internal solution. There were three legs to the stool: there was London, Dublin and Belfast. The London leg and the Dublin leg have effectively fallen away, so the stool is wobbling.”

With a divided leadership in power at Stormont and growing tensions on the ground, any agreement on the past is likely to remain elusive. This makes the task of creating a shared future after conflict even more difficult.

“We don’t have an agreed narrative of the past from which to try to build an agreed vision of the future,” says Norman Hamilton, former moderator of the Presbyterian Church, which campaigned for decades for an end to the sectarian conflict.

“In order to create the political stability, to create enforced power-sharing, the narrative of the past was set aside in the hope that as an executive assembly delivered real progress on the ground the pain of the past would recede. That hasn’t happened.”

This piece originally appeared on Al Jazeera.