Around midnight on July 11, 1995, word reached Srebrenica that Dutch peacekeepers had abandoned their observation posts on the outskirts of town.

The soldiers had arrived in the Eastern Bosnian “safe haven” just over two years earlier, ostensibly to provide a buffer between local Bosniak Muslims and encircling Bosnian Serb forces.

When 19-year-old Hasan Hasanovic heard that the United Nations troops had retreated to their base he knew he had two choices: escape or die.

“I decided to flee through the forest with my father and my brother trying to survive,” says Hasanovic in flawless, clipped English.

He had bartered sugar for English lessons from a local teacher during the three-year-long siege of Srebrenica that ended in July 1995, in the largest act of mass murder on European soil since the Second World War.

Twenty years later Hasanovic works at the Srebrenica Memorial centre, a small museum attached to the sprawling battery factory that once housed the Dutch contingent.

Everyday Hasanovic recounts the same terrible story, nervously turning his wedding ring around his finger as he describes that hot July night when he set off with some 15,000 men to walk more than sixty miles through thick forest to the nearest Bosniak-held town, Tuzla.

The ad hoc human column gathered around six miles outside Srebrenica.

When they started to move Bosnian Serb army units on the overhanging hills began shooting indiscriminately. Hasan Hasanovic was among the crowd pushing forward in panic, desperate to escape the hail of bullets. “I lost sight of my father and my twin brother. Since then I have never seen them,” he told me.

Hasanovic kept walking. A man offered him sugar and water, which he hungrily accepted. The further they walked, the less the men looked at each other, fearful of seeing death etched in one another’s faces.

The following day, around forty miles from Tuzla, they came to rest on a hillside. They had been walking for hours. Some kicked off their shoes, others closed their eyes. Then gunfire ripped through the air.

A thousand men were killed in a matter of moments. Hasanovic managed to break away, seeking shelter in the forest. Below, Serb voices on loudspeakers promised food and safety. Those who surrendered were killed.

Hasanovic walked on. The rubber boots and the hours of wading through streams and forests tore the skin off the soles of his feet. More than once he narrowly escaped Serb militiamen.

“On July 16, after days and nights of being hunted like animals, we reached Tuzla,” he says. The tall chimneys of the industrial city framed a makeshift refugee camp.

The field of white tents seemed to go on forever. People flocked to Hasanovic when they heard he had come from Srebrenica. Had they seen their son, their uncle, their father?

Each time he shook his head dolefully.

Amidst the crowd he spotted his mother, his younger brother and his grandparents. They gripped each other tightly. But there was no sign of his father or his brother.

Of the 15,000 men who set off on the “Death March”, only 3,500 survived. The fate that awaited those that remained in Srebrenica was, if anything, even worse.

Although just a few miles from the Serbian border, Srebrenica had long been a predominantly Bosniak area.

When war broke out, in April 1992, after Bosnia declared its independence, the town’s population swelled as Muslims in the surrounding villages fled the Bosnian Serb offensive to carve out a state of their own from the ashes of the disintegrating Yugoslavia.

Within months some 65,000 refugees had sought refugee in Srebrenica, more than doubling its prewar population.

The Srebrenica enclave was an easy target for the Bosnian Serb army. Attacks were frequent. On April 12 1993, artillery fire hit a school playground. Seventy-four were killed and over a hundred wounded.

Four days later, the United Nations declared the establishment of a “safe haven”.

Life was hard – food was scarce – but the arriving peacekeepers offered protection from the Bosnian Serb forces. Bosniaks gave up their weapons. Fatefully, they were promised they would not need them.

It was beyond our contemplation that the United Nations would betray the people of SrebrenicaHasan Hasanovic

“Everyone had the feeling that they lived in a big concentration camp,” Hasan Hasanovic recalls. “But people were still happy to have anything, to survive. It was beyond our contemplation that the United Nations would betray the people of Srebrenica.”

Srebrenica occupied a crucial strategic position. Without it, the Bosnian Serb dream of creating an ethnically pure state would be stymied. In early 1995, the attacks intensified. Hasanovic’s school was closed again. “Something wrong was coming. People could feel that there was evil in the air.”

This “evil” arrived in early July 1995. The shelling of Srebrenica got worse, much worse. Dutch troops retreated in the face of the Serb offensive.

United Nations commanders initially refused their requests for airstrikes against Serb positions. By the time they relented – dropping just two bombs – Bosnian Serb commander Ratko Mladic had taken peacekeepers hostage.

There would be no full-scale attack on the Bosnian Serb lines. Emboldened by the success, Radovan Karadžić, President of the Serb Republic, ordered his forces to take the town.

In Srebrenica, people began to flee. Almost all able-bodied men began the “Death March”. More than 20,000 sought refugee at the UN compound at Potocari a few miles outside the town.

On July 12, Mladic walked through Srebrenica, handing out sweets to children and mugging for watching television cameras. “No matter if you’re old or young you’ll get transport,” he said. “Don’t be afraid – women and children first.”

The Serb army began separating all men aged 12 to 77, putting them onto buses. At Potocari, Dutch soldiers expelled the Bosniaks sheltering in their base, leading them directly into the hands of the waiting Bosnian Serb military.

Over the next four days, Mladic’s forces killed more than 8,000 men, in Srebrenica.

In a brutal, systematic massacre, victims were shot and clubbed to death in fields and behind houses, in warehouses and abandoned buildings.

Recently released documents suggest the involvement of Greek and Russian far-right fighters in the slaughter.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Court of Justice in The Hague ruled that Bosnian Serbs committed genocide at Srebrenica.

Srebrenica changed the course of the Bosnian war. NATO’s subsequent intervention led to the Dayton peace agreement in December 1995.

Bosnia and Herzegovina was effectively divided into two, between the Croat-Bosniak Federation and “Republika Srpska”. Srebrenica became part of the new Serb Republic.

It took Hasanovic years to find out what happened to his family.

In 2003, his father joined the rows and rows of brilliant white marble headstones at the Potocari graveyard, across the road from the former Dutch base. “In 2005 I buried my twin brother which was the hardest thing in my life.”

A skull missing a mandible sits bolt upright on a stainless steel mortuary slab. Scattered around the head are fragments of bone shaped into a skeletal form. A few ribs, a fibula, two tibias, a handful of fingers. A humidifier hums in the corner.

On the opposite wall, a poster begs “Help Identify Your Loved Ones. Give Your Blood Sample”. The message is written in Bosnian and English.

This small office, in a nondescript business park on the outskirts of Tuzla, is the forensic laboratory of the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP). Funded by international donors, the ICMP was founded at the behest of Bill Clinton at the G-7 summit in 1996.

The commission task was to bring order to the chaos of war by assisting formerly hostile Balkan governments identify and trace some of the 40,000 people missing at end of the Yugoslav wars.

Around 70 per cent of those missing were from Bosnia. In Srebrenica and elsewhere, Bosnian Serb forces used bulldozers to push bodies into unmarked mass graves, which were subsequently exhumed, sometimes multiple times, to hinder identification. Consequently forensic scientists were regularly faced with the kind of scattered remains lying on the Tuzla mortuary table of tenacious Serbian forensic anthropologist Dragana Vucetic.

“When they removed those skeletal remains, often with big trucks, they destroyed the integrity of individuals so very often we don’t find complete bodies, maybe only in 10 per cent of cases,” Vucetic told me.

In the first five years, the ICMP identified just 140 Srebrenica victims, mainly through clothing and body parts. “We had to find another method for investigation. So we made a DNA lab,” says Vucetic.

Blood was collected from tens of thousands of Bosnians, both in the Balkans and across Europe where they had fled as refugees. Within months of the DNA lab opening in 2001, the ICMP had its first positive match. By the close of the following year, it had over 500 more. So far ICMP has identified over 85 per cent of those who died in Srebrenica.

Most victims are buried in the cemetery at Potocari, often during the annual July 11 commemoration.

The process of identification is arduous. Bone samples from victims are taken for DNA testing and matched with profiles on the ICMP database. “We don’t test each bone because that is very expensive. We only test one bone from each sample or each body part,” Vucetic explains as she lifts the heavy door that leads into the cold storage unit. Inside, shelves are lined with the remains of Srebrenica victims, thick plastic body bags on the lower rungs, brown paper bags for clothes and personal possessions above them.

The room has a pungent smell of raw flesh. It reminds me of a long forgotten summer job in a meat factory.

Scattered among the body bags are the remains of 300 individuals awaiting identification. The burden of proof is heavy.

Courts require that DNA matches are 99.95 per cent probability or above. Once a body has been formally identified it is pronounced dead. Family members are contacted.

The ICMP facility is open to the public but they are discouraged from coming to see the remains. “It is very emotional for them to see skeletons. Usually they expect that they will see something else. After 20 years it is still stressful when they come here and see bones,” says Vucetic.

Despite the ICMP’s efforts, almost a thousand people are still missing. It is “most likely” that there is another, so far untraced, mass grave lying amid the verdant Bosnian countryside, says Edin Jasaragic, who works at the ICMP’s main administrative centre, in an old basketball stadium in downtown Tuzla.

Some of those who survived the “Death March” from Srebrenica were inside this austere, Communist-era concrete building. The hard plastic windows are still riddled with bullet holes. On the ground floor, there is a shop that specialises in prosthetic legs. Landmines kill around 20 Bosnians every year.

As well as identifying victims, the ICMP has played a key role in criminal prosecutions. So far 46 individuals have been put on trial at Bosnian state courts for their role in the Srebrenica massacre, including 38 people charged with genocide.

The ICMP’s forensic evidence has also been crucial in the 21 trials related to Srebrenica at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia at The Hague, among them Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladic.

Despite these successes, justice has been “very slow” says Muhamed Durakovic, a Srebrenica survivor who now works for the ICMP in the Bosnian capital Sarajevo. “There are hundreds of people roaming the streets of Srebrenica who are war criminals.”

Someone who took away your child is now working as a police officer or a public official in Srebrenica.Dragana Vucetic

The Hague court has “dealt with the highest ranking individuals but those individuals on an operational level, who actually carried out the killing, are not being dealt with,” says Durakovic. “Someone who took away your child is now working as a police officer or a public official in Srebrenica . To the victims that is totally unacceptable.”

Nevertheless, the ICMP is one of the few genuine success stories to emerge from the impoverished, fissiparous post-war Western Balkans states. Their innovative DNA approach has been exported around the world, helping to identify victims of natural disasters and political violence everywhere from the United States and the Philippines to Chile and Iraq.

“The ICMP has learned a lot in Bosnia over the past twenty years, it has a pool of experts that can deploy anywhere in the world to assist in cases of disaster or war, any time a government needs to identify a large number of individuals” says Muhamed Durakovic, who until recently was stationed in Libya.

Since the ICMP opened, the crucible of human suffering has shifted, to Ukraine, to Syria and numerous other conflagrations.

Silently, Bosnia and Herzegovina, a comparatively small conflict in a relatively unimportant part of the world, has slipped down the international community’s list of priorities.

The ICMP is due to follow the diplomats next year, moving its main operations out of Bosnia. The impecunious Bosnian government is unlikely to step into the breach to fund expensive DNA laboratories.

In a grim irony, the facilities at Tuzla are only likely to remain open if another mass grave is discovered at Srebrenica.

In the 1970s, the Yugoslav government released a promotional video to encourage people to move to the spa town of Srebrenica. Grainy footage shows a gym filled with healthy Bosnians. There is no distinction made between Bosniak Muslims, Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats.

The streets, bounded by tree-lined escarpments, are neat and well tended. It looks for all world like a socialist paradise.

Srebrenica today is a very different place. The once modern apartment blocks are crumbling. Overgrown branches hang across the main thoroughfare. The red, blue and white Serbian tricolour of the Republika Srpska flag hangs limply from a municipal building.

As we drive slowly through town a table full of middle-aged men outside a bar all turn in unison to stare. Srebrenica, on the way to nowhere, is now a by-word for our darkest instincts.

The white minaret of the local mosque still looks down over Srebrenica. Before the war, the vast majority of the town’s 36,000-strong population were Bosniak. Now Srebrenica and the surrounding villages is overwhelmingly Serb.

Some Muslims, however, did take up the option of returning to their former homes afforded under the Dayton agreement, even if it meant living cheek-by-jowl with the men who murdered their loved ones.

In 2002, Hatidža Mehmedović came back to Srebrenica. Her family home had been burned down. Her husband and two sons had been killed. But she was determined to return. “We came here for one reason only, to live with our memories,” Hatidža Mehmedović tells me when we meet under the shade of a large wooden gazebo in the graveyard for Srebrenica genocide victims at Potocari.

Her family’s remains, identified by the ICMP in 2010, are buried nearby.

“They killed everything I had in this world. These are wounds that will never heel,” says Mehmedović, who wears a white headscarf. “This is not a life. This is hell. We returnees, we lost everything.”

Mehmedović is president of Mothers of Srebrenica, an association that represents victims of the massacre. “Many mothers have been left without joy. Our hearts are cold. We will never live to see how it is to see your sons marry. We will never have the joy of holding our grandchildren on our knee, thanks to the United Nations and the great powers.”

The Mothers of Srebrenica launched a legal case against the Dutch peacekeeping forces, arguing that they did not do enough to protect the people in their charge. Last year, a district court in The Hague ruled that the Netherlands is liable for the deaths of more than 300 Bosniak men and boys expelled from the UN base in July 1995.

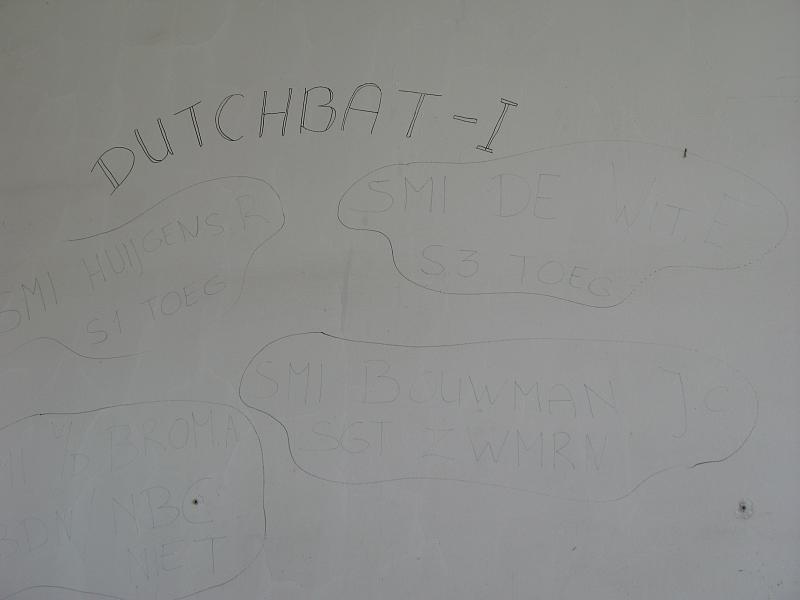

The onetime Dutch military compound still stands at Potocari, across the road from the field filled with slender white gravestones. The Mothers of Srebrenica and others hope to eventually create a huge memorial on the site of the base, but for now it largely stands empty. I climb through an open window into what were once the soldiers’ quarters.

On the walls are crude drawings of naked women and Dutch phrases, untouched in twenty years. In one scrawling, just below a naked couple in bondage gear, there is red heart pierced by an arrow, slowly bleeding.

On July 11, the annual commemoration for the victims of Srebrenica is held at Potocari. This year’s 20th anniversary service was thrown into doubt after Naser Oric, a wartime Bosniak leader in Srebrenica, was arrested in Switzerland.

Oric, a former bodyguard of notorious Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic, is accused of war crimes against local Serbs. The Srebrenica organising committee said the event would be postponed until Oric’s release.

Last week, Swiss authorities announced that Oric would be extradited, but to Bosnia rather than Serbia. The decision caused uproar. Mladen Ivanic, who represents Serbs in Bosnia’s unwieldy tripartite presidency, said he would not be attending the Srebrenica commemoration “in this atmosphere”.

The political wrangling “is setting Bosnia-Herzegovina back to the state of war”, Ivanic added. Serbian president Tomislav Nikolic’s visit to Sarajevo has been cancelled.

Republika Srpska’s president Milorad Dodik went even further. Last week, the pugnacious Bosnian Serb leader, called the Srebrenica massacre ““the greatest deception of the 20th century”.

Previously Dodik, who has ruled Republika Srpska almost unopposed for a decade, has said that, “if a genocide happened, then it was committed against Serb people of this region, where women, children and the elderly were killed en masse.”

Such denial of what happened at Srebrenica, and across Bosnia, runs deep. “Srebrenica hoax” is a popular search term on Google.

Videos on YouTube promise the “real” story of what happened in July 1995, often using language and arguments familiar to Holocaust deniers.

“It is always very difficult to hear stories of denial when we all know what happened, especially those of us who were eyewitnesses to the atrocities and the killings,” says Srebrenica survivor Muhamed Durakovic. “We know what happened to these people. We have seen and witnessed their executions.”

Near Srebrenica, Bosnian Serbs recently put up anti-European Union posters on a warehouse where Bosniaks were killed in protest at a leaked draft United Nations resolution that suggests July 11 should be a memorial day. The resolution, penned by the UK, was vetoed at the UN this week by Russia.

Arguments over Srebrenica are symptomatic of the “polarised” nature of contemporary Bosnia, says Srecko Latal, a Sarajevo-based analyst with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. “This country, this entire region, never initiated its reconciliation process.”

The various international courts established to deal with war crimes in the former Yugoslavia focused too much on legalistic definitions and not enough on building bridges on the ground, says Latal.

The Dayton peace accords created an awkward state structure in which the three ethnic blocs – Bosniak, Serb and Croat – all have effective veto.

In the two decades since the fighting stopped, the recent past has become a political tool, pushing competing ethnicities further and further apart.

“This country is ethnically cleansed,” says Latal. “You don’t have any ethnic mixing anymore in big towns. In schools a majority are mono-ethnic. Kids learn about other ethnic groups from the media and history books and they are all tainted.”

Srebrenica, although fading from many Western memories, still has a resonance beyond Bosnia and Herzegovina’s contested borders.

Less familiar are the countless other massacres: over 5,000, mainly Bosniaks and Croats, were killed in Prijedor in 1992 alone; that same year 3,000 went to their deaths in the eastern town of Visegrad, some of them thrown alive from the town’s bridge; in Zvornik a further 2,000 were killed. The vast majority of this “ethnic cleansing” took place in what is now Republika Srpska.

Last spring, I visited a village called Carakovo, a few miles outside Prijedor in northwestern Bosnia. Before the war, Carakovo’s population was 1,200. Now it is 300.

The only thing that is growing is the graveyard, as more remains are identified and more mass graves discovered. “I feel like the last Mohican here,” Sudbin Music, a community worker who miraculously survived the Serb death camps, told me. “I ask myself, ‘What are you doing? Are you waiting for the next disaster?”

Elmina Kulasić was just a child when she was forced to leave the nearby town of Kozarac. After growing up in Chicago, Kulasić came back to Bosnia three years ago to work with other “returnees”.

The policy of re-settling people in their former homes has been a “failure”, she says. Only a fraction of those who left during the war have returned. “Everyone is ignoring survivors.”

Instead survivors of Bosnia’s vicious war are often used as political footballs.

On July 11, Bosniak politicians will line up with international diplomats and foreign correspondents in the VIP section at the cemetery in Potocari. Afterwards they will make speeches promising “never again.” Then, when the television cameras have stopped rolling, they will get back in their expensive cars, leaving Srebrenica, and its now childless mothers, until next year.

Dayton ended the war but bequeathed a labyrinthine political system structurally disposed to gridlock and stasis. Corruption in Bosnia is rife, according to Transparency International. Political tensions have increased. Dodik regularly threatens Republika Srpska’s secession, potentially splintering Bosnia. Croat politicians agitate for the creation of a “third entity”, centred on Herzegovina with a capital in Mostar. Bosniaks look east for patronage, to Turkey and the Gulf states.

“The political, economic and social situation has got worse since the war,” says Srecko Latal. Meanwhile, the international community has largely switched off. “The European Union is still ignoring that part, if not all, of the Balkans is a boiling powder keg once again.”

Last February, Bosnia did erupt – but not along ethnic lines. Tens of thousands took to the streets demanding jobs, higher wages and a better future. The municipality headquarters in Sarajevo was set alight, as was a government building in Tuzla.

The protests eventually petered out, but the frustrations that underlined them have not. Bosnia’s official unemployment rate is over 40 per cent, even higher among the young.

Average monthly salaries are less than €400. “There is not much hope here,” says journalist Nidzara Ahmetasevic, who lived in Sarajevo throughout the three and a half year long siege of the city.

“During the war it was easier than now. It was simpler. It was a war. They were shooting 24-7. You were scared. You lived like an animal but it was easier. Now you feel all the time under pressure. You feel like you are going to explode but nothing is exploding.”

Resad Trbonja was just 19 when he swapped his Converse trainers and Levi’s t-shirt for a Bosnian army uniform and a place on the frontline defending his native Sarajevo. More than two decades later, he is pessimistic about the future of the country he took up arms to defend.

“We are not going in the direction I was fighting for,” he says. “I didn’t fight for a Muslim country. I fought for Bosnia and Herzegovina, for all its citizens regardless of their faith. I wasn’t prepared for this ethnic division.”

Back at Potocari, a Bosnian state police car is permanently stationed outside the graveyard. On a warm summer’s afternoon there seems little need for such measures. Shirtless workmen toil in the fields beside empty roads. The air filled with the smell of freshly mown grass. Birds sing in the trees.

This idyllic scene belies the political reality. Srebrenica now belongs to Republika Srpska, a state-within-a state whose leaders continue to deny what happened two decades ago. “It is a big hypocrisy that this part of Bosnia where the genocide happened belongs to Republika Srpska,” says Hasan Hasanovic, as a group of Bosnian schoolchildren walk through the Srebrenica memorial. Many are crying.

Six years ago, Hasanovic returned from Tuzla. He now lives in Srebrenica with his wife and young daughter. “Our lives are now a sort of mission. We live everyday trying to bear witness to genocide and all the people who don’t know.”

This piece originally appeared on The Ferret.